You and a friend are having a picnic by the side of a river. Suddenly you hear a shout from the direction of the water—a child is drowning. Without thinking, you both dive in, grab the child, and swim to shore. Before you can recover, you hear another child cry for help. You and your friend jump back in the river to rescue her as well. Then another struggling child drifts into sight… and another… and another. The two of you can barely keep up. Suddenly, you see your friend wading out of the water, seeming to leave you alone. “Where are you going?” you demand. Your friend answers, “I’m going upstream to tackle the guy who’s throwing all these kids in the water.”

—A public health parable (adapted from the original, which is commonly attributed to Irving Zola)

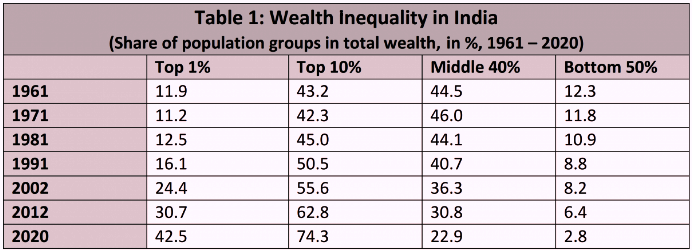

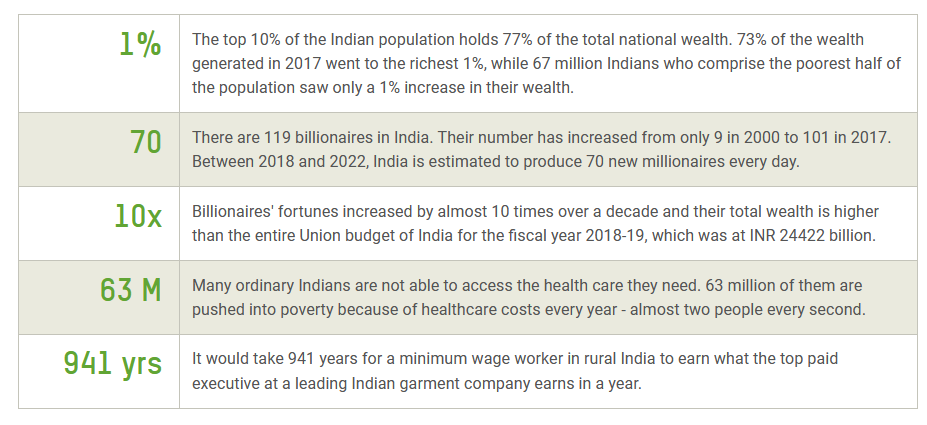

Let us underline, right at the outset, that it is only in the post – The Great Transformation period (à la Karl Polanyi) that one can even begin to fathom the possibility of India’s top billionaires increasing their wealth by 35 per cent while India’s poor population more than doubled from 6 Crore to 13.4 Crore after the first wave of the pandemic. [1] Polanyi argued that before the 19th century, the economic system had been conceived of as a part of the broader society governed by social customs and norms as much as by market principles of profit and exchange. The rise of capitalism, however, involved political efforts to de-link the economy from this social environment. In a market society, basic aspects of social life would be treated as pure market commodities (fictitious commodities) and humans redefined as purely economically rational (i.e., profit-maximising) actors. [2]

Since March 24, 2020, we have been shaken by the images and stories of fellow Indians rendered jobless, hungry, separated from their families, cut off from access to services, and subjected to the most deplorable human conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and national lockdown. The lockdown has made us more aware that the urban poor, especially daily wage earners face starvation if they do not earn daily. As early as May 2020, an estimated 114 million had lost their jobs[3]. This included 91 million daily wage earners and 17 million salary earners who had been laid off across 271,000 factories. 65-70 million small and micro enterprises had come to a halt. The extent of the loss of lives and livelihoods experienced last year is becoming clear “officially” only now, with detailed data from the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) — the latest round of which is for the April-June quarter of 2020.

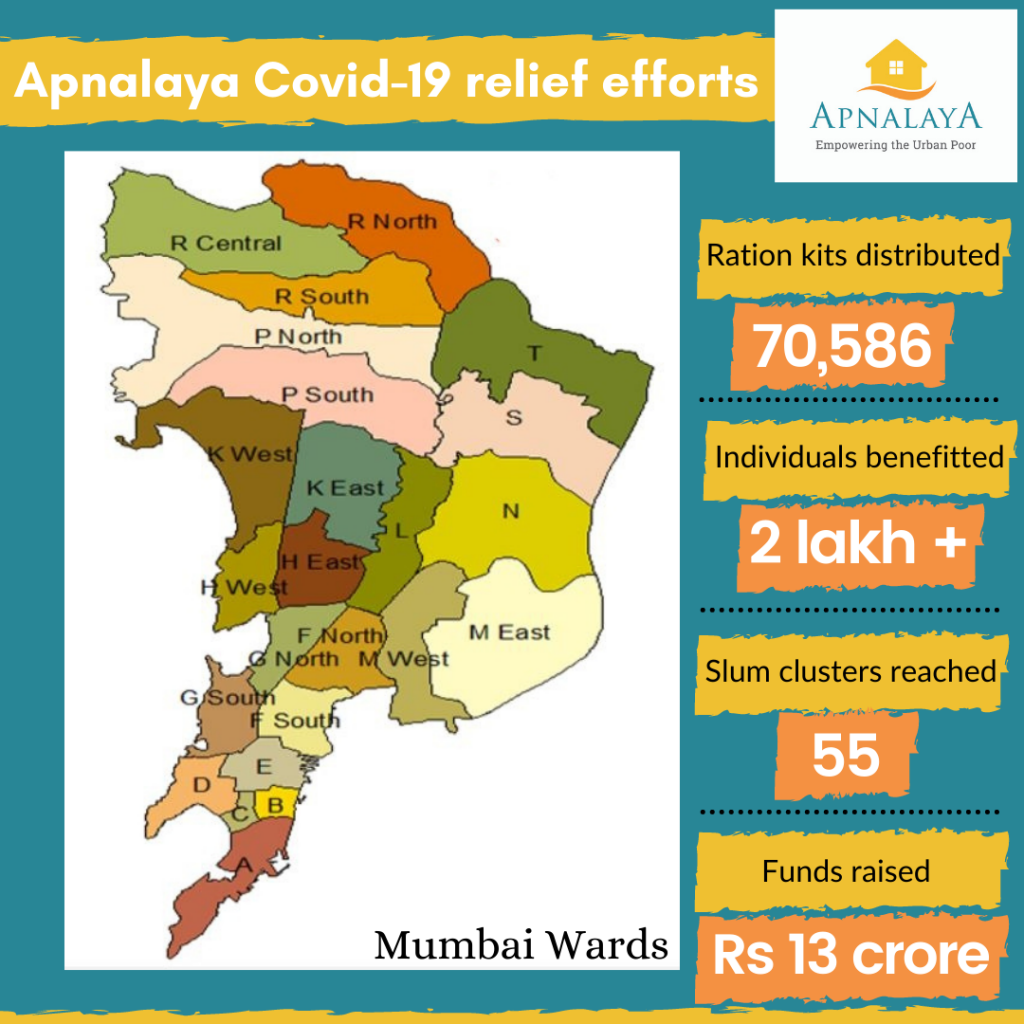

In a recent study conducted by Apnalaya, it was found that in Shivaji Nagar, M East Ward, the average family monthly income was just Rs 13,555—about Rs 2464 per person for the whole month for a family of five. Over 25 per cent of the households do not have ration cards. During the lockdown, 81 per cent of the people have struggled to have access to rations, and 70 per cent had to borrow to buy rations and water. More or less, this is the reality of most of the poor in India. If not for the aid provided by thousands of civil society organisations (CSOs) and citizen groups across the country — supported by an unprecedented philanthropic response from all sections of society — the consequences would have been even more catastrophic.

With no work and little means to support themselves, millions have had no choice but to defy the lockdown and return to their villages. For the urban poor, this has meant more unemployment, food insecurity, indebtedness and further marginalisation. Half of Mumbai lives in slums. The people from Shivaji Nagar slums in the M-East Ward, where a bulk of Apnalaya’s work is focused, share a similar predicament. The Ward has been home to migrants from different parts of India as well as to those who have been resettled from the erstwhile slums situated in the inner recesses of Mumbai. According to the Mumbai Human Development Report, 2009, the Ward has the lowest human development index in Mumbai (24th out of 24 Wards). The average age at death here is 39 years.

In a recent study conducted by Apnalaya, it was found that in Shivaji Nagar, M East Ward, the average family monthly income was just Rs 13,555—about Rs 2464 per person for the whole month for a family of five. Over 25 per cent of the households do not have ration cards. During the lockdown, 81 per cent of the people have struggled to have access to rations, and 70 per cent had to borrow to buy rations and water.[4] More or less, this is the reality of most of the poor in India. If not for the aid provided by thousands of civil society organisations (CSOs) and citizen groups across the country — supported by an unprecedented philanthropic response from all sections of society — the consequences would have been even more catastrophic.

Indian civil society’s COVID-19 response has taken myriad forms. Across the country, individuals, teams, and organisations have provided millions of meals, dry ration kits, and personal protective equipment; amplified health and policy announcements; directed cash transfers and other forms of temporary income support; secured transportation for stranded workers; forged partnerships and coalitions of donors, nonprofits, volunteers, and government agencies; developed research, healthcare, and technology solutions to track, treat, and combat the coronavirus; and advocated on behalf of our democratic rights and freedoms. But has this unprecedented triple crisis — health, economic, and social — changed the approaches of CSOs in some ways?

Changing Roles of CSOs In the very first week that India entered the lockdown in March 2020 to curb the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, Prime Minister Narendra Modi called on CSOs to help the government by providing necessities to the poor, by supplying protective gear, assisting with awareness campaigns on handwashing and physical distancing and, most importantly, reaching rations and cooked food to the unreached.

Credit: Apnalaya Credit: RIF/Maha PECOnet

CSOs across India used their existing grassroots networks and know-how to mitigate the health, economic and social crises in the communities they serve. Several CSOs have also run camps and provided transportation for stranded and starving migrant workers. The Supreme Court has also acknowledged and applauded the role played by CSOs in these moments of the unprecedented pandemic. Development experts believe it is crucial to understand that it would not have been possible for the government alone to holistically address the pandemic — develop, implement and ensure that measures reached the needy, last-mile people. A few have also distinguished between a medical crisis, what the pandemic brought upon us, and a humanitarian crisis, primarily due to abysmal systemic planning, support and provision for the poor.

The drastic change in priorities, that too for a sustained period, as CSOs turned their focus to disaster relief, had a social cost associated with it. Many nonprofits had to suspend their on-ground programmes temporarily and pivot to relief work, and there is fear that this disruption may undo years of efforts and progress, worsened by the funding setback. Short-term suspension of programmes may have a long-lasting impact, especially among marginalised and vulnerable communities.

The second wave, starting in April 2021, highlighted yet another facet of the Indian CSOs. For the first time perhaps, and certainly, at this scale, the CSOs extended their support from their traditional humanitarian work to engaging directly with tasks relating to providing medical infrastructures such as arranging for medical supplies, ventilators, and oxygen cylinders.

The drastic change in priorities, that too for a sustained period, as CSOs turned their focus to disaster relief, had a social cost associated with it. Many nonprofits had to suspend their on-ground programmes temporarily and pivot to relief work, and there is fear that this disruption may undo years of efforts and progress, worsened by the funding setback. Short-term suspension of programmes may have a long-lasting impact, especially among marginalised and vulnerable communities. The disruption in routine and planned programme activities has led to a regression in social development outcomes. With approximately 400 million people employed in the informal economy in India face the risk of slipping deeper into poverty, India estimates a significant impact on Sustainable Development Goals[5]. This may undo years of efforts and progress made by these development organisations.

The drastic change in priorities, that too for a sustained period, as CSOs turned their focus to disaster relief, had a social cost associated with it. Many nonprofits had to suspend their on-ground programmes temporarily and pivot to relief work, and there is fear that this disruption may undo years of efforts and progress, worsened by the funding setback. Short-term suspension of programmes may have a long-lasting impact, especially among marginalised and vulnerable communities. The disruption in routine and planned programme activities has led to a regression in social development outcomes. With approximately 400 million people employed in the informal economy in India face the risk of slipping deeper into poverty, India estimates a significant impact on Sustainable Development Goals[5]. This may undo years of efforts and progress made by these development organisations.

There seems to be a near-total regression as far as the support for entitlements and rights-based work is concerned. The pandemic has signalled the return of the direct service provision approach. The argument of tangible returns is back with most of the corporates and philanthropists. The resource-starved CSOs have no option but to comply. The net impact of this regression is yet to be gauged. What is clear, however, is that civil society organisations have little money to work on civil society itself. The focus on staying with the symptoms is firmly in place. The root causes, working with the Sarkar on basic amenities and entitlements, marginalisation and disempowerment, will increasingly find very few takers in the market.

Fewer Resources, More Restrictions

The resources for the CSOs have shrunk drastically in recent years. Dasra’s research with 250 CSOs from India identified pathways to resilience building over April-Oct 2020. By conducting a detailed study on pre-existing stress drivers amplified by COVID-19, they found that over 40 per cent of CSOs in this period were found to have low resilience to mitigate operationally and financially through 2021. A study by PRIA International Academy, released in May 2020, also found that most grassroots organisations continue to be resource-starved, needing additional human, material and financial resources to continue serving marginalised communities. And now, with the amendments made under the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, introduced in the Lok Sabha on September 20, the sector will be severely impacted as organisations receiving foreign funds will no longer be able to transfer them to small CSOs working at the grassroots level. FCRA money has been going down each year. The Union Minister of State for Home, Nityanand Rai, said CSOs received Rs 16,940.58 Crore in 2017-18, Rs 16,525.73 Crore in 2018-19 and Rs 15,853.94 Crore in 2019-20. He said that the Bill sought to bring transparency and stop the misuse of foreign contributions by people. [6]

This narrative may not hold water. However, the PM-CARES Fund, a charitable trust set up by the Prime Minister in response to the pandemic, also accepts contributions from international donors, is not subject to any scrutiny. Together, they account for more than Rs 15,000 Crores ($2.03 billion), only marginally less than the Rs 16,343 Crores ($2.21 billion) raised by FCRA registered nonprofits last year. The 2020 amendment discourages soliciting foreign contributions and collaborations, provides for stricter penal provisions against CSOs, and detrimentally affects organisations working on advocacy and capacity building.

How Should Bazaar Respond?

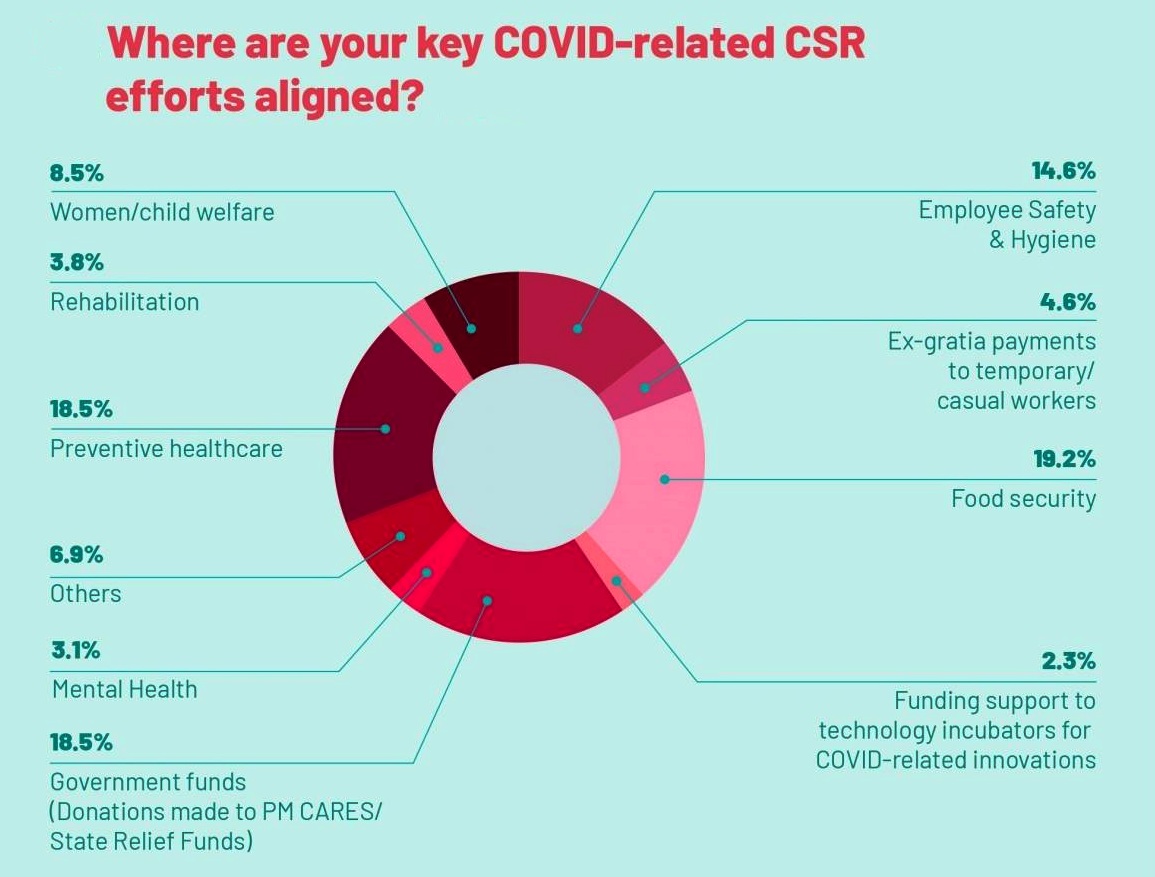

In this changing context of regulations, what role does the bazaar play in social change? This past year, domestic corporations have seen a massive decline in profitability. Domestic corporate giving includes CSR donations and the contribution from Trusts and Foundations. Listed companies’ profitability declined by 62 per cent in the months immediately following India’s initial COVID-19 lockdowns. Therefore, the corpus available for CSR, which grew by 17 per cent from 2014 to 2019, is expected to decline by 5 per cent in 2021[7]. Compounding this challenge, the CSR corpus has shifted away from traditional nonprofits and sectors to the Prime Minister’s Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations (PM-CARES) and other COVID-19 relief initiatives. According to the “ResiLens Stress Test” conducted by Dasra on 125 non-governmental organisations (NGOs), one in two NGOs have an income base that is more than 60 per cent restricted. With funding challenges and long-term CSR partners altering their funding arrangements, these NGOs—already reeling under the impact of reduced foreign funding due to stringent Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) rules—found themselves struggling to survive.

Today, corporates can take a step forward in rebuilding society. It involves a choice between continuing to support targeted benefits to the poor and supporting systemic changes like universal entitlements. As Richard Titmuss said, benefits for the poor end up being poor benefits. The distinction between an act of disaster relief and a path to development must be made clear. Often addressing the symptom of a systemic flaw is taken as social development work, both by the CSOs and the CSR entities. As a society, we are at that critical juncture where the corporates and CSR must commit themselves to a long-term system-correction approach. And, ensuring universal entitlements could certainly be the first step in that direction.

However, the pertinent question here is what exactly are the social responsibilities of the bazaar? There are two types of market social responsibilities: those having to do with social impacts or what bazaar does to society, and those having to do with social problems or what bazaar can do for society. The operational responsibilities (how a market does its business: what sensitivities are shown towards labour and environmental laws, affirmative actions concerning gender, disability, and social backwardness or human rights in general, for instance) cannot be discounted no matter how significantly the social responsibilities (things that companies can do for communities and individuals in need) are cast. The overall responsibility is far greater than just its social responsibility, which, then, is reduced to sharing two per cent of its profit. Typically, social change is a complex inter-generational process[8]. It invariably includes changes at personal (behaviour and practice), social (values and social relations) and systemic (policy) levels. It engages with four elements of everyday life: the individual and her family, the community, the government, and the market.

How many Corporate engagements do we know of where all these elements are touched upon? The bazaar’s response is primarily engaged in questions of poverty and developmental deficits through a service delivery lens. Except for a few, it has not adopted a rights-based systemic approach to analysing and addressing the wicked problems of poverty, injustice and indignity. For example, the caste question, so central to India, is addressed as an issue of developmental deficits and not as a function of the inhuman and oppressive caste system that needs to be dismantled.

One of the leading concerns about their decision to support a social cause is that the Corporates in general do not prefer complex and long interventions. This manifests itself in Corporates expressing a special preference for non-profit organisations with a single-threaded, mono-thematic focus. A holistic intervention, which is more likely to result in sustainable change often falls short in winning their trust and support. One reason why many Corporates tend to focus on the palliative symptoms rather than the root causes would be that it has the potential to become political, and therefore, controversial.

How do we make a deeper, socio-philosophical sense of the choices Corporates tend to make? There seem to be two possibilities. First, we learn that the Corporates’ worldview is still located in the age-old relief where the givers’ energy is primarily focused on themselves. Gifting remains unequivocally about the giver. There is perhaps little consideration of the agency or rights of the deprived and marginalised. Secondly, their penchant for relief and service provision is inextricably tied with their view on the tangibility of a result, which is fashioned by their insistence on immediate evidence on the one hand and instant gratification on the other. Many non-profits, especially those with social entitlements framework, struggle with this dilemma of Relief and Rights. Relief is not always a bad thing though. In any moment of severe crisis or calamity, relief is also a right.

Today, corporates can take a step forward in rebuilding society. It involves a choice between continuing to support targeted benefits to the poor and supporting systemic changes like universal entitlements. As Richard Titmuss[9] said, benefits for the poor end up being poor benefits. The distinction between an act of disaster relief and a path to development must be made clear. Often addressing the symptom of a systemic flaw is taken as social development work, both by the CSOs and the CSR entities. As a society, we are at that critical juncture where the corporates and CSR must commit themselves to a long-term system-correction approach. And, ensuring universal entitlements could certainly be the first step in that direction.

Today, corporates can take a step forward in rebuilding society. It involves a choice between continuing to support targeted benefits to the poor and supporting systemic changes like universal entitlements. As Richard Titmuss[9] said, benefits for the poor end up being poor benefits. The distinction between an act of disaster relief and a path to development must be made clear. Often addressing the symptom of a systemic flaw is taken as social development work, both by the CSOs and the CSR entities. As a society, we are at that critical juncture where the corporates and CSR must commit themselves to a long-term system-correction approach. And, ensuring universal entitlements could certainly be the first step in that direction.

There is an opportunity today with the pandemic for the bazaar to help organisations working on improving the system and be more flexible/open to strengthen organisations not just support projects but to think about the social space and not just a project in the neighbourhood of their industry.

The Way Forward: A Vibrant Public Sphere

The last year and a half have laid bare the great gaps in India’s health, food, sanitation, education, housing and social protection systems. Lack of data on the most vulnerable, especially the urban poor and the informal workers, inadequate access to a job, food, health and other basic social securities, have entered national conscience like never before. In a study published by Vani, it was observed that “In a country like India, the voluntary sector bridges the gap between the government and the population of the country. It identifies the needs of the community and provides its support and services, even in the most untouched and marginalised areas where the government is not able to reach.”

Today, some argue that the problem for governance is the “missing middle”[10] — between spaces for public opinion below, and constitutional forums such as elected assemblies and courts at the top — to find democratic solutions to citizens’ problems. Therefore, building a middle layer of institutions for democratic deliberations amongst citizens has become essential for democratic governance.

The crisis has also brought out in the open the inequities that are reproduced and sustained by caste, gender and class underpinnings of our everyday life. Seizing this window of opportunity, we must bring back our focus on solutions long advocated by civil society. It is about time we revisited the role played by Indian industrialists and businesses during the Freedom Movements. We need nothing less than a renewed attempt at social reconstruction. All we need to do is to look around us and see how we can develop a system that will routinely and institutionally address the question of misery, marginalisation, poverty, hatred, violence, bigotry, and so on.

At Apnalaya, we are in the process of creating a development collective or Samoohik Vikas Samiti. The intent is to facilitate the formation of a more sensitive public sphere led by motivated organic leaders from the community through the formation of SVS, a public platform of disparate individuals and groups invested in a common theme. For example, an SVS on Water or Education will consist of multiple stakeholders in the city – researchers, writers, journalists, policymakers, administrators, CSOs and the local community volunteers working on Water or Education. We aim to redefine civic engagement, access to social entitlements, transparency and accountability of the duty bearers and the government bodies, in such a way that the struggle against marginalisation does not remain the sole concern of the marginalised alone. The sensitive and informed public sphere will ensure that the advocacy of those who live on the margins is shared by those who have voice and visibility as well.

The bazaar should consider strengthening efforts that seek to create and support this “middle”. The pandemic has seen a rise in collaboration between funders, government, and CSOs, resulting in the co-creation of solutions to complex social issues such as hunger, migration, and vulnerable workers. Greater familiarity and trust-building efforts have resulted in greater openness to collaboration.

The crisis has also brought out in the open the inequities that are reproduced and sustained by caste, gender and class underpinnings of our everyday life. Seizing this window of opportunity, we must bring back our focus on solutions long advocated by civil society. It is about time we revisited the role played by Indian industrialists and businesses during the Freedom Movements. We need nothing less than a renewed attempt at social reconstruction. All we need to do is to look around us and see how we can develop a system that will routinely and institutionally address the question of misery, marginalisation, poverty, hatred, violence, bigotry, and so on. We appear to have lost the plot of nation-building. Feeding a hungry child is necessary. However, the distribution of biscuits alone is not going to usher us in a new dawn.

Arun Kumar is the CEO of Apnalaya, a civil society organisation that enables and empowers the urban poor.

Diksha Shriyan works as Project Manager, Citizenship & Advocacy Programme at Apnalaya.

References:

[1]https://www.indiatoday.in/business/story/explained-how-covid-19-crisis-has-exposed-india-s-growing-wealth-gap-1795932-2021-04-28

[2] https://www.britannica.com/topic/embeddedness#ref1181137

[3] https://scroll.in/article/963384/full-text-draconian-lockdown-incoherent-strategies-led-to-india-paying-a-heavy-price-say-experts

[4] Revisiting the Margins: https://apnalaya.org/publications/

[5] https://www.orfonline.org/research/onward-to-the-sustainable-development-agenda-2030/

[6] https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/rs-49000-crore-foreign-funding-to-indian-ngos-in-3-yrsrs-49000-crore-foreign-funding-to-indian-ngos-in-3-yrsnew-delhi-au/2139256

[7] https://thewire.in/business/philanthropy-domestic-firms-ngos-decline

[8] https://idronline.org/are-social-change-and-scale-mutually-exclusive/

[9] https://newleftreview.org/issues/i27/articles/richard-titmuss-the-limits-of-the-welfare-state

[10] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/why-the-citizens-assembly-is-an-idea-whose-time-has-come-7467452/