A life of abundance, raining resources, an unobstructed flow of energy, and a living space bigger than ever is all we want to feel blissful, successful and bountiful. Not so long ago, in the ’90s, we saw and experienced blissfulness and bountifulness in close quarters. A momentary flashback to the life before the millennium takes us back to the most joyous days of our lives – days when everything was not necessarily abundant, resources were not available at the click of a button, power cuts were common, and larger families lived in smaller houses.

Our lifestyle has changed in a short span, and the quantum of resource requirement for the modern lifestyle has grown manifold. Broadly, these resources may be food, energy, land and water. Our modern lifestyle demands these resources in proportions higher than ever before. The risen and further rising demand for all such resources puts us face to face with a fundamental question. How long can we sustain a consumption-driven society?

India is committed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) for 2030. The Government of India (GoI) promotes various flagship programmes towards the fulfilment of the SDGs. They include the Swachh Bharat Mission, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, Smart Cities, among others. However, without a change in the consumeristic attitude and a shift to a mindful sustainable lifestyle among citizens, GoI schemes may not achieve their full potential.

The question of sustainability runs parallel with urbanisation. As our urban centres grow, they need to be constantly fed with resources. The global urban population outnumbers the global rural population, and by 2050, two-thirds of the world population would be living in its urban centres. India is one of the least urbanised nations, yet the urban population in India is the second-largest in the world. India’s urban population will further grow with 250 million urbanites by 2030. India is committed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) for 2030. The Government of India (GoI) promotes various flagship programmes towards the fulfilment of the SDGs. They include the Swachh Bharat Mission, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, Smart Cities, among others. However, without a change in the consumeristic attitude and a shift to a mindful sustainable lifestyle among citizens, GoI schemes may not achieve their full potential.

Shifting the urban lifestyle to a sustainable one starts with first understanding its consumption and waste-producing trends. As urban dwellers, we are large scale consumers as well as waste producers. We need to twitch both ends together to ensure the sustainability of our habitats. Municipal waste from cities adds up into huge piles and ends up at large waste deposit sites in the suburbs of our cities. These waste mounts not only occupy land area but also emit huge amounts of greenhouse gases. These waste hills are a threat to urban health and sanitation as well. The solution to this problem is waste segregation at its point of source, i.e., households. A simple, easy to adopt solution yet, hardly practised. Waste from the kitchen can be composted easily in bins at home.

Shifting the urban lifestyle to a sustainable one starts with first understanding its consumption and waste-producing trends. As urban dwellers, we are large scale consumers as well as waste producers. We need to twitch both ends together to ensure the sustainability of our habitats. Municipal waste from cities adds up into huge piles and ends up at large waste deposit sites in the suburbs of our cities. These waste mounts not only occupy land area but also emit huge amounts of greenhouse gases. These waste hills are a threat to urban health and sanitation as well. The solution to this problem is waste segregation at its point of source, i.e., households. A simple, easy to adopt solution yet, hardly practised. Waste from the kitchen can be composted easily in bins at home.  Of the total municipal waste generated in cities, more than 50 per cent is biodegradable, and 17 per cent is recyclable. This considerable proportion of waste can be avoided from taking up space in landfills and waste mounts if segregated and treated wisely. Municipal authorities operate solid waste management (SWM) plans, but they are not sufficient. SMW needs to be aided by the active participation of individual citizens through the golden 5R approach – reduce, reuse, recover, recycle and remanufacture.

Of the total municipal waste generated in cities, more than 50 per cent is biodegradable, and 17 per cent is recyclable. This considerable proportion of waste can be avoided from taking up space in landfills and waste mounts if segregated and treated wisely. Municipal authorities operate solid waste management (SWM) plans, but they are not sufficient. SMW needs to be aided by the active participation of individual citizens through the golden 5R approach – reduce, reuse, recover, recycle and remanufacture.

Since most of us have witnessed the ’90s and have seen how our parents sold all household non-biodegradable discards to the recyclers instead of adding them to municipal waste, it should not be hard for us to revert to the old system. Understandably, the recycler networks have eroded and need to be re-established. The Government must promote small scale entrepreneurs for such recycling businesses.

The 5R approach, if adopted well, can also help in significantly reducing the demand for natural resource extraction, thereby reducing the adverse impacts on natural ecosystems. Before the 5R term was coined, Indians already had been beautifully using their network of kabadiwallas, essentially recyclers of all non-food discards. After the economic boom in the ‘90s, we have been spoilt with use and throw marketing gimmicks and a massive lineup of products.

A society that inherently uses more and recycles less turns into a consumeristic waste-producing society. A simple example is the packaged drinking water in plastic bottles. They  have entered our households and offices at such a massive scale that we have almost forgotten the good old humble earthen water pot. Since most of us have witnessed the ’90s and have seen how our parents sold all household non-biodegradable discards to the recyclers instead of adding them to municipal waste, it should not be hard for us to revert to the old system. Understandably, the recycler networks have eroded and need to be re-established. The Government must promote small scale entrepreneurs for such recycling businesses.

have entered our households and offices at such a massive scale that we have almost forgotten the good old humble earthen water pot. Since most of us have witnessed the ’90s and have seen how our parents sold all household non-biodegradable discards to the recyclers instead of adding them to municipal waste, it should not be hard for us to revert to the old system. Understandably, the recycler networks have eroded and need to be re-established. The Government must promote small scale entrepreneurs for such recycling businesses.

As citizens, we must take small but steady steps towards switching from the ‘use and throw’ products to ‘use, reuse, sustain’ ones. Compost our kitchen waste and sell non-biodegradables to the recyclers. It is encouraging to note that there are so many bloggers promoting sustainable ways.

A flashback to the ’90s also reminds us of our roads, which were not as densely filled with carbon-emitting vehicles as they are today. A large section of the community commuted using bicycles, cycle-rickshaws and on foot. Depending upon affordability, most of us now commute via petroleum-fueled two-wheelers, four-wheelers and public transport. Vehicular emissions not only cause global warming but also degrade the air we breathe.

Switching to the humble bicycle is not the last stop solution for few practical reasons. Our roads do not have cycling lanes; bicycles may not cater to all age groups (depending upon fitness); they are weather-dependent for ease of use, and they may take a longer time. On the other hand, upon switching to the bicycle, we may save up on rising fuel costs, and even our gym membership fees. A more practical and long-term solution lies in electric vehicles, which is steadily making their way into the Indian market. This industry needs to evolve faster to cater to the urban commuter. The Government needs to enhance public transport facilities and promote their use via incentives as free passes and tokens.

Among the various aspects of leading a sustainable life, water consumption demands the highest level of mindfulness and responsibility as it is a basic and sometimes free resource. Technological innovation around water conservation is very encouraging, but policy intervention to mandate using such technologies is required to steer the public mindset towards water as a precious commodity.

Water. The ’90s reminds us of how precious a resource it is. We were taught to use it wisely. Mere every day habits can help us conserve water. Though large urban centres have well-connected water supply systems, smaller towns and rural areas still have immense scope for water connectivity, but it may not be possible without reducing the consumption of household water in cities. Human habitats in urban and rural areas must adopt water conservation techniques like roof harvesting, greywater recycling, using recycled water for non-consumption purposes, pressure reducing valves, efficient taps and nozzles, leak-free pipes and metered water.

Among the various aspects of leading a sustainable life, water consumption demands the highest level of mindfulness and responsibility as it is a basic and sometimes free resource. Technological innovation around water conservation is very encouraging, but policy intervention to mandate using such technologies is required to steer the public mindset towards water as a precious commodity. As citizens, we may begin with small steps as closing the taps when not in use, installing systems to recycle water for use in gardens and washing, installing powerful nozzles, and tapping rainwater.

Our Government is making efforts in meeting the SDGs through various programmes. But the last baton of this relay lies in the hands of us, the citizens. Taking small steps in our daily lives may help in making the human habitat more sustainable.

Talking of electricity, the energy that powers our urban habitats, without which our urban lives would come to a complete standstill, is the actual elephant we never really discuss. We tend to think of electricity as the greener alternative to petroleum and gas. It is because electricity is that intangible entity produced in areas far away from urban habitats. We seldom ponder over the process of electricity production.

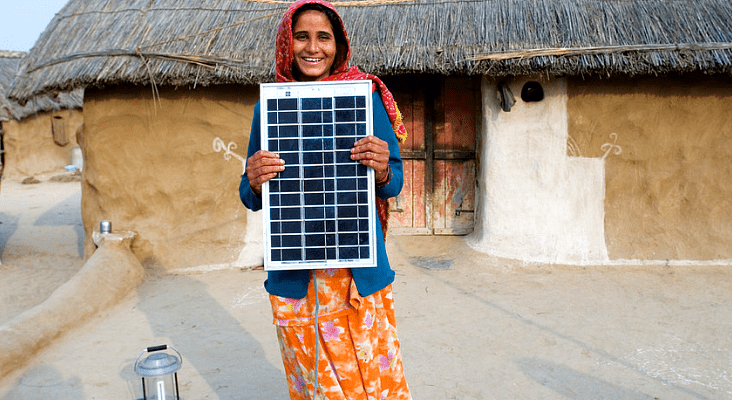

India generates over 60 per cent of its electric power in thermal plants which use fossil fuels and often flout emission norms. Before we think that we made greener choices by switching to electric alternatives for cooking and vehicles, we must bear in mind the scale of carbon emissions made for producing electricity. Switching to greener electricity, i.e., renewable energy at the household level, has already become commonplace, and wider adoption of it in the human habitat will take us closer to the SDGs.

The Government must incentivise low consumption of electricity under a ceiling and penalise over a certain limit, as is done in some European nations. Installation of solar panels must be encouraged through government schemes. Needless to say, as consumers of electric power, we must practise mindfulness and wisdom in a typical ’90s conduct.

The Government must incentivise low consumption of electricity under a ceiling and penalise over a certain limit, as is done in some European nations. Installation of solar panels must be encouraged through government schemes. Needless to say, as consumers of electric power, we must practise mindfulness and wisdom in a typical ’90s conduct.

Our Government is making efforts in meeting the SDGs through various programmes. But the last baton of this relay lies in the hands of us, the citizens. Taking small steps in our daily lives may help in making the human habitat more sustainable.

Priyamvada Bagaria is a landscape ecologist. She is currently freelancing as a GIS Consultant.