The Olympics this year witnessed the most successful outing in terms of medal count for India. This feat would not have been possible without the extraordinary efforts of the sportsmen and sportswomen who showed the world their mettle at the highest level of their discipline. After a 41-year wait, the Men’s Hockey Team finally won an Olympic medal. Shuttler PV Sindhu proved once again that she is one of the best in the world at her craft by becoming only the second Indian to win two individual medals at the Olympics. Neeraj Chopra won India’s last medal in Tokyo, but the first-ever at any track and field event at any Olympic games. However, in the excitement and jubilation of the victories, there were a few stories or rather parts of a few stories that were either omitted or overlooked by the mainstream.

Weightlifter Mirabai Chanu opened India’s medal account with a silver in the women’s 49 kg category – her first medal at the Olympics, but not the first of her career. It surprises me that not much has been mentioned about her achievements in the 2017 World Weightlifting Championship where she won a gold medal in the women’s 48 kg category or how she won India its first gold in the 2018 Commonwealth Games and broke the games record for the weight category. It seems that our fascination with any other sports other than cricket only lasts till a major sporting event like the Olympics is ongoing and our heroes are quickly sidelined for more mainstream stars till the next major sporting event is around the corner.

The story is almost the same barring a few details; it is of a system that does its best to recognise talent but somehow fails to work optimally, and only the few that are fortunate enough to grind past their hardships make it to the top. It almost makes one wonder how many of these stories are currently playing out in our country. With a population of over one billion and 41 per cent of those under the age of eighteen, one cannot stop and wonder about the amount of talent that goes unrecognised or the potential future champions that will have to give up their dreams due to financial, personal or familial reasons.

Lovlina Borgohain was another success story to come out of the North East with her bronze medal win at the women’s welterweight event, becoming only the third Indian boxer to achieve a podium finish at the Olympics. Her achievements were recognised by her State Government and other organisations with deserved rewards, but again little has been written about the struggles her family had to endure for her to reach here, with her mother taking loans from the local cooperative to secure her daughter’s name in the history books.

Similarly, freestyle wrestler Ravi Kumar Dhaiya who won the silver medal in the 57 kg category did not let the financial hardships of his family get in the way of his success. Other than his struggle of helping out his family with their work and pursuing a career in wrestling, his father, a small farmer from Sonipat, Haryana, travelled 39 km every day from their village to the stadium to deliver fresh milk and fruits, which were part of his wrestling diet, for more

Similarly, freestyle wrestler Ravi Kumar Dhaiya who won the silver medal in the 57 kg category did not let the financial hardships of his family get in the way of his success. Other than his struggle of helping out his family with their work and pursuing a career in wrestling, his father, a small farmer from Sonipat, Haryana, travelled 39 km every day from their village to the stadium to deliver fresh milk and fruits, which were part of his wrestling diet, for more  than a decade. Wrestler Bajrang Punia became the third Indian debutant to win a medal at the Olympics this year. Like Chanu, Borgohain and Dhaiya, Bajrang too faced many challenges and financial hardships to reach where he is now. The story is almost the same barring a few details; it is of a system that does its best to recognise talent but somehow fails to work optimally, and only the few that are fortunate enough to grind past their hardships make it to the top. It almost makes one wonder how many of these stories are currently playing out in our country. With a population of over one billion and 41 per cent of those under the age of eighteen, one cannot stop and wonder about the amount of talent that goes unrecognised or the potential future champions that will have to give up their dreams due to financial, personal or familial reasons.

than a decade. Wrestler Bajrang Punia became the third Indian debutant to win a medal at the Olympics this year. Like Chanu, Borgohain and Dhaiya, Bajrang too faced many challenges and financial hardships to reach where he is now. The story is almost the same barring a few details; it is of a system that does its best to recognise talent but somehow fails to work optimally, and only the few that are fortunate enough to grind past their hardships make it to the top. It almost makes one wonder how many of these stories are currently playing out in our country. With a population of over one billion and 41 per cent of those under the age of eighteen, one cannot stop and wonder about the amount of talent that goes unrecognised or the potential future champions that will have to give up their dreams due to financial, personal or familial reasons.

In the past few decades, there have been multiple opportunities as a nation to come around the concept of an equal opportunity sports ecosystem – a system where no sport is given preference in terms of infrastructure and popularity amongst the masses; a system where talent is given its due in terms of exposure, world-class training, nutrition, and financial aid. However, lack of initiative and competent management and a structural handicap between the key stakeholders has allowed certain sports to take precedence over others. The failure to recognise talent at an early age at the grassroots level has been a crucial factor for India’s lacklustre performance compared to other major countries like the  USA, China, Japan and Great Britain in the past decades. With a school and college-going population of 411 million, it is safe to say that there is ample talent in India raring for proper infrastructure and training opportunities to show their worth at the international level. Former Indian Olympian Anju Bobby George recently said in an interview that the inability to compete with the best of the best on the biggest stage in the world is due to lack of exposure to top-level competitions, hampering our chances at better performances at track and field events. It should come as a shock that the world’s second-most populous nation has one of the worst Olympic records in terms of medals per head. A chronic lack of resources has undermined India’s performances for decades though this is not the only reason for India’s sub-par performances.

USA, China, Japan and Great Britain in the past decades. With a school and college-going population of 411 million, it is safe to say that there is ample talent in India raring for proper infrastructure and training opportunities to show their worth at the international level. Former Indian Olympian Anju Bobby George recently said in an interview that the inability to compete with the best of the best on the biggest stage in the world is due to lack of exposure to top-level competitions, hampering our chances at better performances at track and field events. It should come as a shock that the world’s second-most populous nation has one of the worst Olympic records in terms of medals per head. A chronic lack of resources has undermined India’s performances for decades though this is not the only reason for India’s sub-par performances.

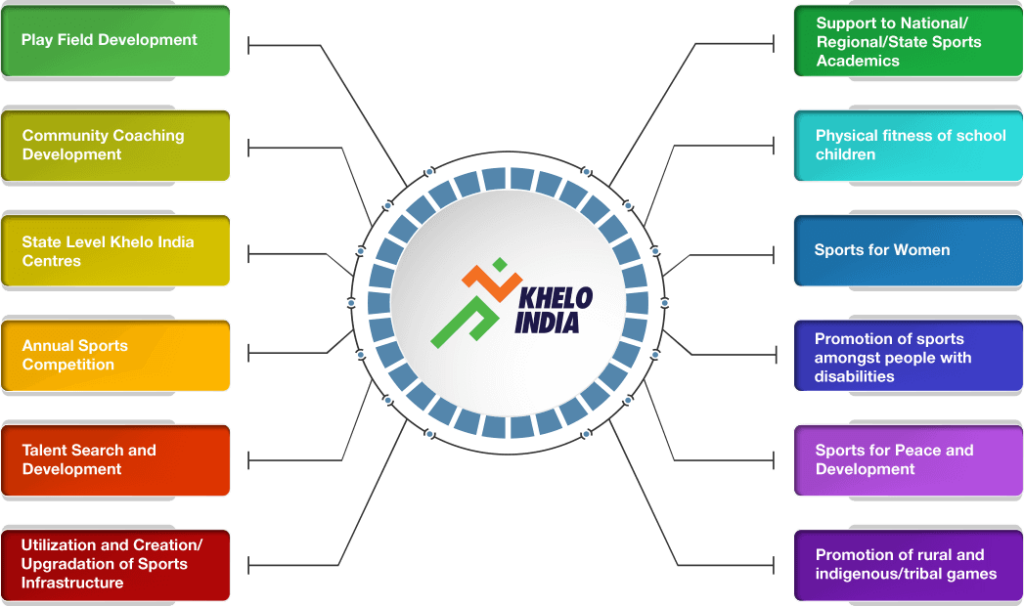

Khelo India, one of the most extensive grassroots level initiatives by any Indian government in the past, is a multidisciplinary event for the Under-17 and Under-19 categories. Every year, 1,000 players are given an annual scholarship of Rs 5 Lakh for eight years to prepare them for international sporting events. It is also supplemented by a Training of Trainers (TOT) programme where 160 trainers are trained in four batches of 40 each, once a year.

Sports is hardly the priority in a majority of Indian households. Most Indian parents would prefer their children to become engineers, doctors, lawyers, or secure government jobs compared to a career in sports. This is primarily due to a lack of means, financial gains, and job security. However, the current government has taken a keen interest in sports and has implemented several sports initiatives to curb these challenges. The Target Olympics Podium Scheme (TOPS) is one such initiative that must be credited for India’s most successful Olympic campaign. To put medal winners on the podium, TOPS engaged reputed sportspersons to identify potential medal winners by an objective process, with the selected athletes guaranteed complete support through customised programmes delivered professionally, bypassing bureaucratic delays.

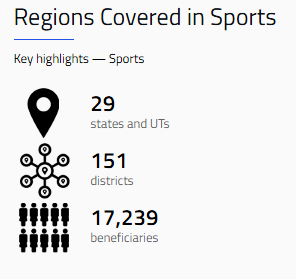

Khelo India, one of the most extensive grassroots level initiatives by any Indian government in the past, is a multidisciplinary event for the Under-17 and Under-19 categories. Every year, 1,000 players are given an annual scholarship of Rs 5 Lakh for eight years to prepare them for international sporting events. It is also supplemented by a Training of Trainers (TOT) programme where 160 trainers are trained in four batches of 40 each, once a year. Programmes like these not only provide potential talent with a better shot at success at the highest level, but also provide the existing talent, trainers, coaches, and support staff with employment opportunities within the sports ecosystem. However, these schemes need to be supported by private initiatives, and there should be supplementary feeder programmes that ensure the right and most deserving talent gets to make the most out of these government initiatives.

Khelo India, one of the most extensive grassroots level initiatives by any Indian government in the past, is a multidisciplinary event for the Under-17 and Under-19 categories. Every year, 1,000 players are given an annual scholarship of Rs 5 Lakh for eight years to prepare them for international sporting events. It is also supplemented by a Training of Trainers (TOT) programme where 160 trainers are trained in four batches of 40 each, once a year. Programmes like these not only provide potential talent with a better shot at success at the highest level, but also provide the existing talent, trainers, coaches, and support staff with employment opportunities within the sports ecosystem. However, these schemes need to be supported by private initiatives, and there should be supplementary feeder programmes that ensure the right and most deserving talent gets to make the most out of these government initiatives.

According to a BBC report, each medal Great Britain won in the 2012 Olympic Games cost the country an estimated average of 4.5 million Sterling Pounds. According to other reports, the scale of China’s sports sector is set to reach nearly CNY 3 trillion (62 Billion USD) by the end of this year, with the Chinese government investing 10 Billion Yuan (approx. 1.5 Billion USD) in 2019, ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. To compete with these kinds of figures, it is not only essential for the private sector to step in and lend their support to the national cause through CSR and other initiatives but a great opportunity for sports start-ups to seek investments from bigger corporations looking to enter the untapped sports market.

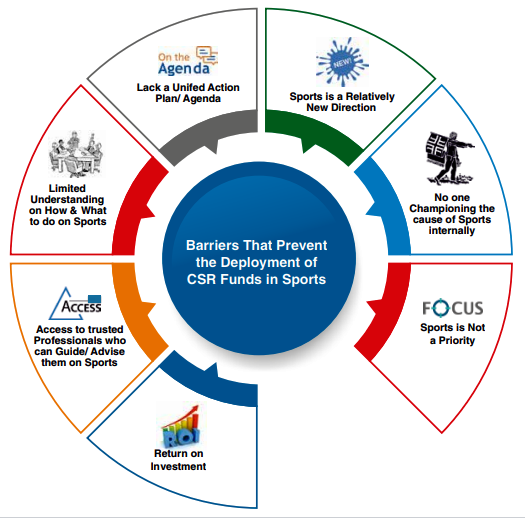

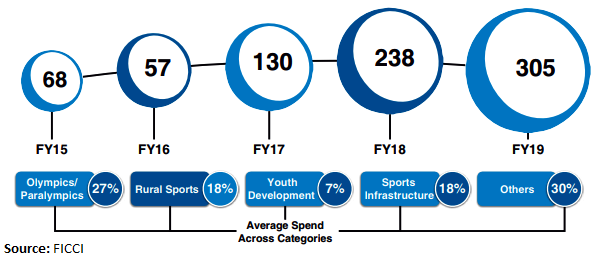

Corporate India only spent INR 795 Crores out of INR 49,600 Crores towards Sports between FY 2014 and FY 2019, which amounts to a meagre 1.6 per cent of the total CSR spend. Barring a few names, a vast majority of the corporate sector has long ignored sports as a viable option in terms of CSR. Tata has been one of the leaders in promoting sports in India. Ever since the ’80s, Tata has shown great interest in the development of the sports sector. Be it the inception of the Tata Football Academy in 1987, Tata Archery Academy in 1996, or Jamshedpur Football Club (JFC) in 2017. Tata has always led the way when it comes to sports.

To compete with the kind of resources that other leading nations back their sports system, a more concentrated effort is needed at the grassroots level by implementing centralised training and nutrition programmes that focus on grooming talent from a young age and seeing that the said talent has all the means necessary to advance to the professional level.

The JSPL Foundation (Jindal Steel and Power) is another example of CSR impacting the sports ecosystem. Apart from providing training and nutrition, the Foundation also undertakes maintenance of stadiums and promotion of sports in rural and tribal areas. But perhaps one of the most notable initiatives in recent times is the Sports Excellence Program by JSW Foundation (JSW Group) which has been integral in Neeraj Chopra’s gold medal win at the Olympics this year.

The Inspire Institute of Sports (JSW Group) is India’s first high-performance training centre imparting training in five Olympic disciplines. Situated in Karnataka and spread over 42 acres, the Institute brings together 23 corporate donors, and as the name suggests, is truly an inspiring initiative. Other major corporations like Reliance, Hindustan Zinc and Central Coalfields Ltd have also taken an interest in sports. However, the efforts of these corporations may not be enough for us to reach our country’s full potential.

To compete with the kind of resources that other leading nations back their sports system, a more concentrated effort is needed at the grassroots level by implementing centralised training and nutrition programmes that focus on grooming talent from a young age and seeing that the said talent has all the means necessary to advance to the professional level. Tailor-made curriculums and infrastructure must be available to the youth to explore sports as a viable career option from a young age and set them up for a better chance of success at higher levels of competition.

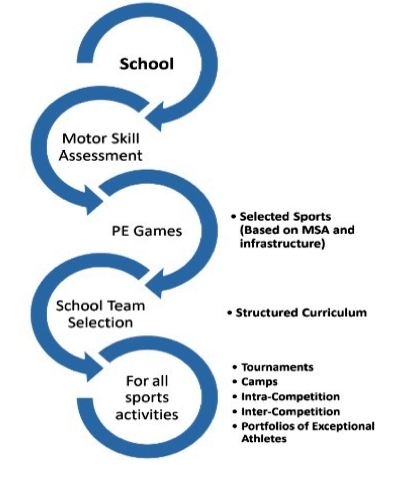

One such model that could be explored is setting up Individual School Group Leagues within a network of schools such as Army schools, various Corporate Group schools (Birlas, Jindals, Ambani, Adani), DAVs, Kendra Vidyalaya, MCD, etc. This will not only ensure regular training and participation but also provide an opportunity to identify talent at the national scale from a specific pool of participants, which in turn promotes competitiveness and holds trainers and coaches accountable to a certain extent.

Many start-ups are willing to provide operational support for the implementation of such programmes. However, not much interest has been displayed by the corporate sector. One such start-up, SportVolt Pvt Ltd., implemented its pilot project at Army Public School, Dhaula Kuan, New Delhi. The project involved outsourcing the complete sports department of the school to SportVolt Pvt Ltd and running it through their Curriculum Integration Model with minor upgrades in infrastructure and focus of scientifically designed training/coaching practices in over 35 games.

Another model that has already proven to be successful is the outsourcing of the entire sports department of a specific school. By bringing in accomplished sportspersons, trainers and other support staff, the existing sports department of a school is upgraded by investing in the infrastructure and developing and deploying tailor-made sports curriculums with regular updating and training of trainers.

An alternate model worth exploring is the ‘hub and spoke’ model for Government/MCD schools, where one school in a specific city/district is chosen as a ‘hub’ where world-class infrastructure is installed with the help of CSR funds. The schools acting as ‘spokes’ would be trial grounds where scientifically crafted training programmes, trails/leagues and other supporting activities are held to identify talent. With the assistance of CSR, the selected talent will be allowed to pursue the remainder of their education at the ‘hub’ where their boarding and nutritional needs would be taken care of as part of a sports scholarship.

An additional possible CSR model could be the running of self-sustaining evening sports academies at Government/Private Schools in Tier 1 and 2 cities as most of the schools grounds are available in the evening. With an initial investment in a school’s infrastructure and deployment of professional trainers/coaches, these academies would be free of charge or available at highly subsidised rates for the selected school’s students while charging a standard fee for all outside students. These models should be supported with capacity building initiatives that ensure employment within the proposed programmes. Trainers must be abreast with the latest training/coaching and conditioning practices and provided with the means to implement the same, thereby increasing the chances of their pupils to perform better. Digital management systems should be employed to track the progress of players and trainers alike.

Many start-ups are willing to provide operational support for the implementation of such programmes. However, not much interest has been displayed by the corporate sector. One such start-up, SportVolt Pvt Ltd., implemented its pilot project at Army Public School, Dhaula Kuan, New Delhi. The project involved outsourcing the complete sports department of the school to SportVolt Pvt Ltd and running it through their Curriculum Integration Model with minor upgrades in infrastructure and focus of scientifically designed training/coaching practices in over 35 games. This also included providing digital solutions for monitoring, assessment and tracking athletes’ programmes and services. Within a year, they were able to groom 95 Zonal/Inter-Zonal players, 35 national level players and also fed five students in Khelo India and other leagues. However, with the change in school management, the programme was discontinued after the pilot project ran for a year. This is a very common challenge when schools are funding such programmes out of their own pockets.

Many start-ups are willing to provide operational support for the implementation of such programmes. However, not much interest has been displayed by the corporate sector. One such start-up, SportVolt Pvt Ltd., implemented its pilot project at Army Public School, Dhaula Kuan, New Delhi. The project involved outsourcing the complete sports department of the school to SportVolt Pvt Ltd and running it through their Curriculum Integration Model with minor upgrades in infrastructure and focus of scientifically designed training/coaching practices in over 35 games. This also included providing digital solutions for monitoring, assessment and tracking athletes’ programmes and services. Within a year, they were able to groom 95 Zonal/Inter-Zonal players, 35 national level players and also fed five students in Khelo India and other leagues. However, with the change in school management, the programme was discontinued after the pilot project ran for a year. This is a very common challenge when schools are funding such programmes out of their own pockets.

With the success of government-funded initiatives and India’s recent performance at the Tokyo Olympics, I am hopeful that the CSR sector will come together and support the sports ecosystem. It is more important than ever to invest in the potential of our country’s youth and adopt a holistic approach and recognise the value of sports and the place it will hold in the future of our nation.

With the success of government-funded initiatives and India’s recent performance at the Tokyo Olympics, I am hopeful that the CSR sector will come together and support the sports ecosystem. It is more important than ever to invest in the potential of our country’s youth and adopt a holistic approach and recognise the value of sports and the place it will hold in the future of our nation.

Colonel Prakash Tewari is an Armed Forces veteran. A UNESCO awardee, he has served as Director Policy (Ecology) in Government of India, Head of CSR – Rehabilitation and Resettlement of Tata Power Company Limited, Executive Vice President, CSR and Education – Jindal Steel and Power Limited, and Executive Director – CSR for DLF Ltd. He was responsible for mitigating social and environmental risks of large infrastructure development projects in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Australia. He is presently the Chairman of Tewari Group Pvt Ltd. Sport Volt Professional Services is one of the initiatives of Tewari Group.